Information and Guidance for Specific Safeguarding issues

Scope of this chapter

This chapter provides helpful information and guidance around the following specific safeguarding issues:

- Pressure ulcers;

- Medication errors;

- Safeguarding people with Dementia;

- Missing persons;

- Carer to person abuse and neglect;

- Domestic abuse;

- Self-neglect and hoarding;

- Mate crime and cuckooing (forced home invasion);

- Online abuse and harassment;

- County lines;

- Radicalisation and violent extremism;

- Honour based abuse and forced marriage.

Relevant Regulations

Regulation 12: Safe care and treatment

Regulation 13: Safeguarding service users from abuse and improper treatment

Related Chapters and Guidance

- Accidents, Injury and Incidents

- Safe Care and Treatment

- Supporting People with Complex Needs and Specific Conditions

- Safeguarding and Deprivation of Liberty

- Skills for Care: Guide to adult safeguarding

- NICE: Safeguarding adults in care homes

- Skills for Care: Pressure ulcers

- NICE: Helping to prevent pressure ulcers

- Department of Health and Social Care: Pressure Ulcers: how to safeguard adults

- NICE: Managing medicines in care homes

- NICE: Managing medicines for adults receiving social care in the community

Amendment

Section 6, Domestic Abuse was updated in November 2024 to add a clearer explanation of controlling or coercive behaviour.

A pressure ulcer (sometimes referred to as a pressure sore) is an injury to the skin and underlying tissue, primarily caused by prolonged pressure on the skin.

Pressure ulcers usually form on bony parts of the body, such as the heels, elbows, hips and tailbone.

Signs of a pressure ulcer include:

- Discoloured patches of skin that do not change colour when pressed – the patches are usually red on white skin, or purple or blue on black or brown skin;

- A patch of skin that feels warm, spongy or hard;

- Pain or itchiness in the affected area of skin.

Pressure ulcers usually develop gradually but can sometimes appear over a few hours.

They can become a blister or open wound. If left untreated, they can get worse and eventually reach deeper layers of skin or muscle and bone.

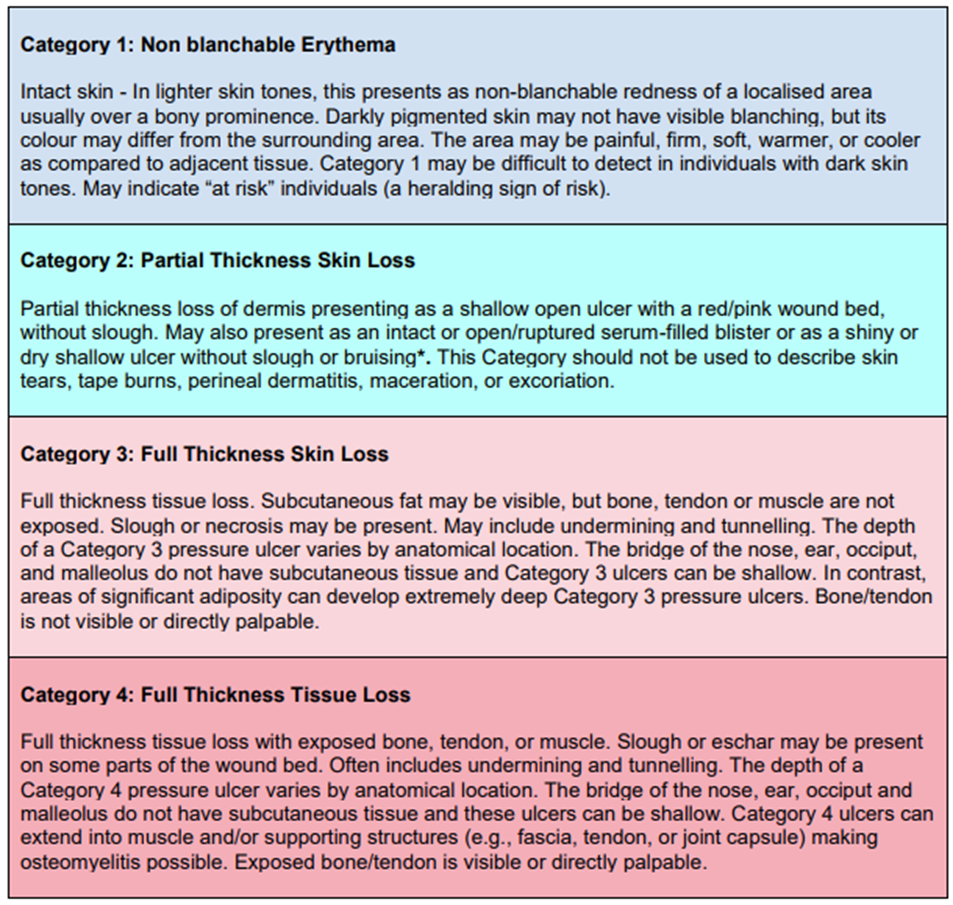

Once diagnosed, pressure ulcers are categorised by health professionals as either category 1, 2, 3 or 4.

Source: National Wound Care Strategy Programme

According to the NHS, people have a higher risk of getting a pressure ulcer if they:

- Have problems moving;

- Have had a pressure ulcer before;

- Have been seriously ill in intensive care or have recently had surgery;

- Are underweight;

- Have swollen, sweaty or broken skin;

- Have poor circulation or fragile skin;

- Have problems feeling sensation or pain.

It is vital that any assessments carried out by the service consider the risk of pressure ulcers developing. This could be prior to starting the service but also applies to any reassessment or review carried out when, for example, a person is discharged from hospital.

If the assessment identifies that someone is at high risk of developing a pressure ulcer, a person-centred risk assessment should be carried out to identify preventative measures and strategies that could be used to manage risks. A health professional, such as a suitably experienced nurse should always be involved in this risk assessment.

See: Risk Assessment (Person-centred)

Preventative measures could include:

- Regular repositioning;

- Supporting and encouraging people to stay active;

- Using specially designed mattresses and cushions;

- Checking skin daily for early signs;

- Using barrier creams to improve skin integrity;

- Maintaining good standards of continence care;

- Having a healthy diet with enough protein, vitamins and minerals.

If someone is at high risk of developing a pressure ulcer, body maps should be completed as part of daily monitoring of skin integrity.

Wherever possible, people using the service should be able to make their own decision about the preventative measures that are put in place to manage risks. If they lack capacity, this decision must be made in their best interests, usually by the health professional involved in the risk assessment. Where the risk of a pressure ulcer is lower, the registered person may be responsible for making this decision, which they should make with full regard to any health advice and recommendations.

A person with capacity to make decisions relating to their risk of pressure ulcers may decide to manage risks without support (to self-care). If this is the case, it is important that a health professional establishes all the following:

- They understand any advice given to them;

- They can put the advice into practice;

- They have the necessary equipment they need (and know how to use it);

- They understand the implications of not following advice.

If it later appears to staff that the person is unable to self-care or manage the risk, a record of concerns should be made, and urgent medical advice should be sought to reduce the risk of a pressure ulcer developing.

Recording and reviewing risk and preventative activity

All risks and preventative measures must be clearly set out in the individual care or support plan and communicated to staff. All staff providing care and support to the person must understand the risks, how to monitor for early signs that a pressure ulcer may be developing, how to record pressure areas on a body map and when/how to seek medical advice or intervention.

Risks relating to pressure ulcers should be reviewed whenever an assessment, care or support plan is reviewed or whenever there is (or may have been) a change in need. For example, if staff observe a person to have lost weight or become less mobile. If there is already a pressure ulcer risk assessment in place, the health professional that was involved in this should be involved in any review or reassessment.

If someone is at risk of developing a pressure ulcer, it is vital that we all know the early signs that an ulcer may be developing. This will help us to get early medical intervention and reduce the risk of the area developing into something painful, something that requires hospital treatment or even something that becomes life-threatening.

Signs of a pressure ulcer include:

- Part of the skin becoming discoloured (red, purple or blue);

- Discoloured patches that do not change colour when pressed – the patches are usually red on white skin, or purple or blue on black or brown skin;

- A patch of skin that feels warm, spongy or hard;

- Pain or itchiness.

If any of the above symptoms are present, medical advice should be sought and a clinical assessment requested as soon as possible, normally from the person’s GP. This should be done with the consent of the person, although it should also be done if the person withholds consent. We have a duty of care to reduce unnecessary risk of harm occurring.

Records of all concerns and the medical advice/attention sought and provided must be made.

If the person has a pressure ulcer and is experiencing any of the following symptoms, call 999:

- Red, swollen skin;

- Pus coming from the pressure ulcer or wound;

- Cold skin and a fast heartbeat;

- Severe or worsening pain;

- A high temperature.

The clinical assessment

As part of seeking medical advice or attention, the service must arrange for a clinical assessment to be carried out by a clinician with experience in wound management, normally a nurse.

Following their assessment, the nurse must decide whether the person has a pressure ulcer and ensure they have access to the right medical treatment. Where a pressure ulcer is present, they must also decide whether they have any safeguarding concerns. If they do, they should complete the adult safeguarding decision guide (see below). This will help determine whether a safeguarding concern should be raised to the local authority.

If the service is a nursing home, the registered nurse on duty can carry out the clinical assessment, so long as they were not involved in providing care to the person at the time that the pressure ulcer developed. If this is the case, another nurse must complete the assessment.

If there are additional safeguarding concerns (not solely related to the potential pressure ulcer), a safeguarding concern should be raised prior to the completion of the clinical assessment.

The adult safeguarding decision guide

If a clinical assessment has concluded that there are safeguarding concerns, the nurse should complete the adult safeguarding decision guide immediately afterwards or within 48 hours.

The tool contains 6 questions that together will indicate a safeguarding decision guide score. The professional judgement of the nurse should always be used to make the final decision, but a guide score of 15 or more would normally indicate that a safeguarding concern should be raised to the local authority.

For guidance on completing the guide and to download the relevant documentation, refer to the government guidance: Pressure ulcers - how to safeguard adults.

Regardless of the outcome, a copy of the completed decision guide must be kept on the person’s file.

How to raise a concern

Safeguarding concerns should be raised in line with the requirements and processes of the local authority.

The safeguarding concern can be raised by the nurse that completed the adult safeguarding decision guide, or, in agreement with the nurse, by the registered person (or designated safeguarding lead).

Whoever raises the concern, the local authority must be provided with a copy of the completed clinical assessment and adult safeguarding decision guide documentation.

After reviewing the information it receives, the local authority will decide whether enquiries under Section 42 of the Care Act 2014 should be instigated and/or what investigative action is required by the service and others (for example, any health professionals involved in the care or treatment of the person).

Delays in either the clinical assessment or the completion of the adult safeguarding decision guide should not lead to delays in raising a safeguarding concern. If you believe that abuse or neglect has (or may have) taken place, a concern should be raised.

Action when a safeguarding concern is not raised

If it is decided that a safeguarding concern does not need to be raised to the local authority, it does not mean that no other action is required.

All clinical recommendations to treat or prevent pressure ulcers must be incorporated into risk assessments and care or support plans.

Where relevant, the nurse must ensure that any training and ongoing health intervention/support/monitoring is provided.

Staff must seek further medical advice or attention should there be a deterioration in the person’s pressure ulcer, or there are signs of any new pressure areas developing.

Any notifications required under law must also be made. This could be to the CQC, commissioners or to relevant people under the Duty of Candour.

CQC notifications

CQC must be notified when the pressure ulcer has resulted in any of the following:

- A death;

- A serious injury;

- A safeguarding concern being raised;

- A report being made to, or an investigation by the police.

See: Notifications

Commissioners

If the terms of the contract between the service and the commissioning organisation requires a commissioner to be notified, they must be notified.

Duty of Candour

The duty of candour requires the service (and every individual employee) to be open, honest and transparent, including when things go wrong. If the duty of candour applies, information must be shared with the ‘relevant person’ as set out in the duty of candour process.

For guidance on the duty of candour. See: Duty of Candour.

All staff should receive training in preventing pressure ulcers and recognising signs of developing pressure ulcers.

The National Wound Care Strategy Programme has developed a free workforce programme with the NHS. This e-learning programme aims to support the health and care workforce in developing the knowledge and skills required in any setting.

See: Wound Care Education for the Health and Care Workforce Programme.

The National Patient Safety Agency defines a medication error as

“A patient safety incident involving medicines in which there has been an error in the process of prescribing, dispensing, preparing, administering, monitoring, or providing medicine advice, regardless of whether any harm occurred”

Some examples of medication errors:

- Omissions – prescribed dose not given;

- Wrong dose administered - too much or too little;

- Medication given to the wrong person;

- Extra dose given;

- Wrong dose interval e.g., medication that should be given at 4 hourly intervals is given after 3 hours;

- Wrong administration route;

- Wrong time for administration;

- Not following ‘warning’ advice when administering e.g., take with or after food;

- Administration of a drug to which the person has a known allergy;

- Administration of a drug past its expiry date or which has been stored incorrectly.

In all cases, the safety of the person should be the primary concern. Medical advice must be sought, including emergency advice if there appears to be an adverse reaction or side effect from the error that has been made.

Once the person is safe, the error and any urgent action taken to safeguard the person must be properly recorded and reported to the registered person.

See: Accidents, Injuries and Incidents

Records should be made as close to the time that the incident occurred as possible.

If the medication error is a safeguarding issue, a concern must be raised to the local authority (see below).

Any other notifications required under law must also be made. This could be to the CQC, commissioners, your local Controlled Drugs Accountable Officer or to relevant people under the Duty of Candour.

CQC notifications

CQC must be notified when the medication error has resulted in any of the following:

- A death;

- A serious injury;

- A safeguarding concern being raised;

- A report being made to, or an investigation by the police.

See: Notifications

Commissioners

If the terms of the contract between the service and the commissioning organisation requires a commissioner to be notified, they must be notified.

Controlled Drugs Accountable Officer

Incidents relating to controlled drugs must be reported to your local Controlled Drugs Accountable Officer at NHS England.

The current register of accountable officers can be found on the CQC website:

Controlled drugs accountable officers

Duty of Candour

The duty of candour requires the service (and every individual employee) to be open, honest and transparent, including when things go wrong. If the duty of candour applies, information must be shared with the ‘relevant person’ as set out in the duty of candour process.

For guidance on the duty of candour. See: Duty of Candour

Medication errors can be accidental or intentional.

All errors require a safeguarding concern to be raised whenever the safeguarding duty is met and any of the following applies:

- The error triggers the requirement for a CQC notification (see below);

- The error has resulted in actual harm;

- Medication has been used as a form of unlawful restraint e.g., a non-prescribed sedative is given;

- Medication has been administered covertly;

- The prescription instructions are not followed;

- Consecutive errors for the same person i.e., more than one does in a row is missed;

- Multiple errors for the same person;

- A single error or multiple errors that affect multiple people;

- Repeated errors made by the same staff member;

- PRN medication given outside of medical guidance.

Medication errors made by others, for example the pharmacy or the GP should also be reported if the safeguarding duty applies.

If you are not sure whether a medication error is safeguarding, raise a safeguarding concern or seek advice from the local authority safeguarding team.

NHS England defines a near miss as "a prevented patient safety incident". In other words, the person’s safety would likely have been compromised if someone hadn’t acted in time to avoid the error being made.

Near misses do not need to be raised as a safeguarding concern. Neither does any other notification need to be made.

Even if they are not managed through a formal safeguarding process, all medication errors and near misses must be properly investigated by the registered person. This should be done in collaboration with staff. Opportunities to reduce future risk and improve practice must be identified and acted upon.

For further guidance, see: Learning from Safeguarding Enquiries, Safety Incidents and Complaints

As Dementia progresses, the common symptoms intensify, making people with the condition at increased risk of abuse or neglect over time.

These symptoms are:

- Loss of memory;

- Difficulty in understanding people and finding the right words;

- Difficulty in completing simple tasks and solving minor problems;

- Mood changes and difficulties managing emotional responses.

1. Loss of memory

Someone with Dementia may not remember what has happened to them, for example how they sustained an injury or why they are upset. Their memory of events can also become confused-they may think something happened when it did not. This can make it difficult to understand exactly what has or has not happened and to take appropriate action to manage future risks.

A person with Dementia can also forget where they live, where they are, or where they are going when out in the community. This can make them vulnerable to exploitation and abuse from strangers, but also to risks from the environment (e.g., cold temperatures, rain etc.), from hunger/thirst and from not taking medication on time.

Someone with Dementia may forget to eat, drink, take their medication, have a wash or get dressed. Alternatively, they may eat too much or take too much medication. This can cause unintentional self-neglect.

As their condition progresses, a person with Dementia may forget how to control essential bodily functions, such as swallowing, continence and motor functions, such as walking or standing up. This provides a greater number of opportunities for abuse or neglect to occur.

2. Difficulty understanding people and finding the right words

Someone with Dementia may remember what has happened and know that it is wrong but can find it hard to explain this to someone else. They could also struggle to understand questions asked of them or information shared with them. Because of this, they can be more easily coerced into doing something that they do not actually want to do or that puts them at increased risk of harm.

If a person with Dementia cannot find words, they can resort to behaviours such as shouting, screaming, pushing and hitting out. This can increase the risk of abuse through the retaliation of the person that has been pushed/hit/shouted at.

3. Difficulty in completing simple tasks and solving minor problems

As a person with Dementia becomes more dependent on others for all aspects of life, this increases the burden on those supporting them. When carers and staff in provider services feel under pressure and/or unsupported the risk of unintentional or intentional abuse or neglect increases.

Depending on their own awareness of their diminishing capabilities, the person with Dementia can become frustrated and angry. They can resent or refuse to be supported, which can increase the risk of harm or self-neglect.

4. Mood changes and difficulties managing emotional responses

Someone with Dementia may have unpredictable mood changes, which can be quite intense. Often, they will not respond to a situation or piece of information in the same way that people without Dementia would respond. For example, they may laugh at a funeral or start sobbing uncontrollably during a happy family event. This can make the behaviour appear inappropriate to others and cause embarrassment to anyone with the person. Attempts to control the person’s behaviour as quickly as possible can lead to unintentional or intentional abuse.

All the following are examples of ways that we can reduce the risk of abuse or neglect occurring:

|

Reduce the risk of injury from the environment - slips, trips, falls |

|

Use the Herbert Protocol |

|

Consider technology to monitor safety and enable tasks to be completed safely |

|

Communicate effectively - ask for SALT support if needed |

|

Use correct moving and handling techniques - ask for OT support if needed |

|

Develop effective and least restrictive responses to mood changes and behaviours - ask for Clinical Psychology support is needed |

|

Support carers to access their own support services e.g., carers assessment, support from Alzheimer’s Society |

|

Liaise with the commissioning organisation if needs are increasing and more support is needed |

It does not matter that the person has Dementia - if a person has an injury, or if they are distressed and the reason for that injury or distress cannot be easily explained, a safeguarding concern must still be raised.

Reporting will enable an appropriate and proportionate enquiry to take place. This will uncover any hidden abuse or neglect and highlight measures that are needed to help the person and their network of support to manage the risk of ongoing/future harm.

Information and guidance about people going missing is provided in another chapter of this Handbook:

If the person lives in the community and is also supported in any way by a family member or friend, that person is a carer under the Care Act 2014.

It does not matter whether the carer lives with the person or visits to provide support. It also does not matter whether they provide support through every day, or only now and again.

Some carers enjoy their role and can balance it well with other areas of their life. Some carers do not enjoy the role or find it more challenging to prevent the caring role from having a negative impact on other areas of their life, or on their own physical or mental wellbeing.

When a carer is struggling, the risk of intentional or unintentional abusive or neglectful behaviour towards the person being supported increases. Abusive or neglectful behaviour can often be a sign of carer breakdown. This is the point at which the carer can no longer care effectively or with compassion.

There are factors that can increase the risk of carer-person abuse or neglect:

|

The person’s health and care needs exceed the carer’s abilities |

|

The carer has little insight or understanding into the person’s condition or needs and how best to support them |

|

The person treats the carer with a lack of respect, courtesy or appreciation |

|

The person refuses to engage in activities that would give the carer respite, such as respite breaks or attendance at day activities. |

|

The person is abusive or threatening towards the carer |

|

The carer has little or no personal or private space/time |

|

The carer has no network of support - emotional or practical |

|

The carer has made significant sacrifices because of the caring role e.g., given up work, stopped going to the gym, stopped travelling |

|

The carer has unmet or unrecognised needs of their own, such as physical health issues or family problems |

|

The carers says that they ‘cannot do this anymore’ or things like ‘I hate my life’ |

|

The carer frequently requests help and support |

Information and guidance about reducing the risk of carer to person abuse and neglect is provided in another chapter of this Handbook:

It does not matter whether we have sympathy for the carer and understand the pressure they are under - if the person being supported has an injury, or if they are distressed and the reason for that injury or distress cannot be easily explained, a safeguarding concern must still be raised.

Reporting will enable an appropriate and proportionate enquiry to take place. This will uncover any hidden abuse or neglect and highlight measures that are needed to help the person and the carer manage the risk of ongoing/future harm.

Domestic abuse is defined as “abusive behaviour between two people aged 16 years or above that are personally connected to each other, regardless of whether the behaviour consists of a single incident or a course of conduct (pattern of behaviour”.

The term ‘personally connected’ means any of the following:

- They are, or have been, married to each other;

- They are, or have been, civil partners of each other;

- They have agreed to marry one another;

- They are, or have been in an intimate personal relationship with each other;

- They each have, or there has been a time when they each have had, a parental relationship with the same child;

- They are relatives.

Behaviour is abusive if it consists of any of the following:

- Physical or sexual abuse;

- Violent or threatening behaviour;

- Controlling or coercive behaviour (see below);

- Economic abuse;

- Psychological, emotional or other abuse.

Controlling or coercive behaviour is an intentional pattern of behaviour used by one person (the perpetrator) for the purpose of exercising power and control over another (the victim).

Examples of controlling or coercive behaviour include:

- Controlling or monitoring daily activities;

- Acts of force to persuade the victim to do something against their will;

- Isolating the victim from family, friends and other sources of support;

- Threats and intimidation.

Where certain criteria are met, controlling and coercive behaviour is a criminal offence.

Domestic abuse must always be treated as a safeguarding concern when the safeguarding duty applies. If in doubt, raise the concern.

When a safeguarding concern is raised, the person experiencing the abuse will have quick access to specialist local Domestic Abuse Services and, where proportionate a MARAC response can be instigated.

What is MARAC?

MARAC stands for ‘Multi-Agency Risk Assessment Conference’.

The MARAC is a meeting where agencies talk about the risk of future harm to individuals experiencing domestic abuse and draw up a multi-agency action plan to help manage that risk.

Agencies at the MARAC will include:

- The police (normally Chairing the conference);

- Health;

- Local authority children's services;

- Housing;

- Independent Domestic Violence Advisors (IDVA's);

- Probation;

- Local authority adult services;

- Other specialists as relevant.

Self-neglect can broadly be defined as one or more of the following:

Lack of self-care

This includes neglect of personal hygiene, nutrition and hydration, or health, to an extent that may endanger safety or wellbeing.

Lack of environment care

This includes situations that may lead to domestic squalor or elevated levels of risk in the living environment (e.g., health or fire risks caused by hoarding).

Refusal of assistance

This might include, for example, refusal of care services or of health assessments or interventions, even if previously agreed, which could potentially improve self-care or the home environment.

Hoarding involves the acquisition of items with an associated inability to discard things that have little or no value (in the opinions of others) to the point where it interferes with the use of living space or activities of daily living. For example, that limits activities such as cooking, cleaning, moving through the house and sleeping. It could also potentially put the person and others at risk from fire.

Do not assume that self-neglect or hoarding is a lifestyle choice, or the way in which a person wants to live their life. In most cases, it isn’t.

Some people may self-neglect or hoard because they are unable to care for themselves due to, for example, a physical or cognitive disability.

Some people self-neglect as a result of trauma, loss or bereavement. A person may have been neglected or abused, may be experiencing domestic abuse, or may have had significant loss in their life. This trauma or loss may have affected their self-esteem, self-worth and ability to self-care.

It is important to recognise that our own views about self-neglect and hoarding will be grounded in, and influenced by, personal, social and cultural values and we should always reflect on how our own values might be affecting our judgement.

Finding the right balance between respecting the person’s autonomy to live their life how they wish and meeting the duty to protect their wellbeing is vital.

Not all self-neglect issues are safeguarding issues. It may be possible to work with the local housing authority or fire service to try to resolve hoarding issues. It may be possible to liaise with the local authority if the level of service being commissioned does not appear to be adequate to meet the person’s needs.

A safeguarding concern should be considered if there is a risk that the person’s behaviour could have serious consequences for either the person or others, and the person does not understand, cannot manage (or does not acknowledge) the risk of that negative impact occurring.

A safeguarding concern must be raised if the safeguarding duty applies. If in doubt, raise the concern.

Once a safeguarding concern has been raised, the local authority can instigate a multi-agency enquiry and work with a range of agencies to address specific causes of the self-neglect or hoarding behaviour and support the person to manage the risks and make changes to improve their quality of life and wellbeing.

Mate crime is the inappropriate befriending of a person by an individual or individuals with the intention of exploiting or abusing them.

Examples of exploitation include:

- Stealing money or goods;

- Forced labour;

- Coercion into spending money or giving away possessions;

- Coercion into prostitution or other sexual acts;

- Coercion to commit criminal offences e.g., buying/selling drugs.

In the early stages of mate crime, the individual will usually behave in ways that build rapport and trust with the person, homing in on the material and/or emotional things that the person in question genuinely needs or desires. For example, buying them gifts, spending quality time with them, giving them drugs or alcohol.

Once befriended, the individual can use a range of abusive or harmful behaviour towards the person, either to abuse / neglect them, or to ensure their compliance with exploitation: For example:

- Threats of harm;

- Saying things to create feelings of worthlessness or dependency;

- Actual physical assault or restraint;

- Withholding medication or possessions important to the person;

- Covert or overt use of drugs or alcohol.

They may also be using positive incentives to control the person. For example, buying them gifts, socialising with them and making them feel valued.

The abuse or exploitation often happens in private, and the 'relationship' may appear on the face of it to be genuine to both the person and their networks of support.

Cuckooing occurs when the individual that has befriended the person moves in, takes over the property, and uses it to grow or distribute drugs, or as a base for other illegal activities such as prostitution. The person is often manipulated or forced to become involved in the illegal activity against their will.

Those targeted are usually socially isolated or living on their own. This is clearly intentional on the part of the individual befriending them, as it reduces the likelihood that the behaviour will be challenged by others.

This does not mean that people who live with others (e.g. in a care home) or in a family environment are not at risk. Social media platforms provide a gateway to these people that can also be exploited to befriend them online in the same way as befriending in person.

|

Changes in behaviour (e.g., becoming more withdrawn or increase in risk taking) |

|

Changes in appearance (taking less or more care, weight loss) |

|

Financial difficulty (e.g., bills not paid, unable to buy food) |

|

Changes to household environment (e.g., missing possessions, rubbish, unusual items such as cigarettes, alcohol) |

|

Changes in routine and regular activities |

|

Withdrawing from existing networks of support and services |

|

Unexplained injuries |

|

Secretive or increased mobile phone or social media use |

|

Talking about new 'friends' |

|

Suddenly changing a will |

|

Frequent visitors, an increase in people entering and leaving |

|

Possible increase in anti-social behaviour in and around the property |

If there is a risk to the personal safety and wellbeing of staff these risks should be assessed, and measures put in place to reduce them. This should be agreed in collaboration with relevant staff members.

The main prevention measures are to build the person’s resilience and develop their ability to form positive relationships (and recognise a bad relationship) and to stay safe online and in the community.

Information and guidance about both these strategies is provided in another chapter of this Handbook:

Online abuse is where the abuser uses the internet to target a person for the purpose of exploiting or harassing them.

Examples include:

- Email;

- Text and other messenger services;

- Social media platforms including Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp, X, Instagram, Snapchat and LinkedIn;

- Websites;

- Online gaming platforms;

- Online date and relationship sites e.g., Plenty of Fish, Tinder.

Some of the most common abusive behaviours online are:

Trolling: Posting insults, provocation or bullying the person online.

False representation: Pretending to be someone else, often by stealing an identity.

Grooming: Using the internet in a predatory fashion, to try to lower a person’s inhibitions or heighten their curiosity about sex, with the aim of eventually meeting them in person for the purposes of sexual activity. This can include online chats, sexting, (sending and requesting inappropriate texts or images of a sexual nature), and other interactions.

Cyber stalking: Stalking someone online or using technology to track their movements.

Phishing: Sending emails or texts pretending to be from a reputable company, in order to get a person to reveal personal information. For example, passwords and credit card numbers. This is financial abuse.

What is illegal offline is also illegal online - this makes online abuse a safeguarding issue. If the safeguarding duty applies, a safeguarding concern must be raised.

The person should be encouraged and supported to block any numbers that are sending them direct messages to their mobile device.

If abuse or harassment is taking place on a social media platform, the person should be supported to contact the platform and raise a complaint.

The following types of online abuse and harassment behaviours are criminal acts and should also be reported to the police:

- Online stalking;

- Harassment;

- Sending malicious communications;

- Improper use of a public electronic communications network;

- Revenge pornography.

The main prevention measures to reduce risk are to build the person’s resilience and develop their ability to form positive online relationships (and recognise a bad relationship) and to stay safe online.

Information and guidance about both these strategies is provided in another chapter of this Handbook:

The government defines County Lines as:

“A term used to describe gangs and organised criminal networks involved in exporting illegal drugs into one or more importing areas within the UK, using dedicated mobile phone lines or other form of “deal line”. They are likely to exploit children and vulnerable adults to move and store the drugs and money and they will often use coercion, intimidation, violence (including sexual violence) and weapons.”

County Lines gangs are highly organised, using sophisticated and frequently evolving techniques to groom victims and to evade capture by the police.

Dedicated mobile phone lines or “deal lines” are used to help facilitate County Lines drug deals.

Gangs use the dedicated mobile phone (“deal lines”) to receive orders and contact victims to instruct them where to deliver drugs.

A few of the phrases that a victim may use when involved include:

- ‘Running a line’;

- ‘Going OT/out there’;

- ‘Going county’;

- ‘Going cunch’.

These all refer to going out of town to deliver drugs or money.

Some of the other indicators that a person being supported may be involved in County Lines activity could include:

- Going missing from home, an unwillingness to explain their whereabouts and/or being found in areas they have no obvious connections to;

- Anti-social behaviour or involvement in other criminality;

- Unexplained items like clothes, money or mobiles;

- Increase in the number of calls/texts and/or having multiple sim cards or phones;

- Carrying or storing weapons;

- Possession of a rucksack or bag that they are very attached to or will not put down;

- Isolation from usual social networks;

- Spending increased amounts of time online day and night;

- Unexpected or excessive sharing of personal information online;

- Threats of intimidation to other residents or neighbours.

As a service, if we have any worries about County Lines, we must call the police and raise a concern to the local authority.

For further information, see:

National Crime Agency: County Lines

GOV.UK: Criminal exploitation of children and vulnerable adults – county lines

Radicalisation is the process by which people come to support terrorism and extremism and, in some cases, to then participate in terrorist activity.

Radicalisation is a process rather than an event. Some people may be influenced by family members or friends and/or direct contact with extremist groups or organisations. Others may view online content, in particular social media, that can normalise radical views or promote violent extremism.

The following could all be indicators that a person we support may be a victim of radicalisation:

- General changes of mood, patterns of behaviour, secrecy;

- Changes of friends and mode of dress;

- Spending an increased amount of time online;

- Use of inappropriate language;

- Possession of violent extremist literature;

- The expression of extremist views;

- Planning to take long term holidays and visits out of the UK;

- Advocating violent actions and means;

- Association with known extremists;

- Seeking to recruit others to an extremist ideology.

There is an obvious difference between supporting radical and extreme views and acting on them. Holding radical or extreme views is not illegal – what is illegal is the act of committing an offence or inciting others to do so in the name of that belief or view.

If anyone thinks a person we support may be involved in radicalisation and there is an immediate risk of harm to others, call 999 straight away.

If it isn’t an emergency, report your concerns to the police (using 101) or the Anti-Terrorism hotline. They will decide the best course of action:

Tel: 0800 789 321

If the safeguarding duty is met, a safeguarding concern must also be raised.

Any advice given by the police, or the Anti-Terrorism hotline must be recorded and followed as a matter of national security.

Further information

Honor based abuse (sometimes referred to as ‘Honour Crime’ or ‘Izzat’) is abuse carried out when a family or community believes the person has behaved in a manner that undermines what they consider to be the correct code of conduct.

Punishments can include assault, false imprisonment, rape, forced abortion, threats to kill and sometimes even murder.

In the multi-agency statutory guidance for dealing with forced marriage, forced marriage is defined as:

“A marriage in which one or both spouses do not consent to the marriage but are coerced into it. Force can include physical, psychological, financial, sexual and emotional pressure.”

It also includes marriages where one or both individuals are unable to provide consent. For example, because they have a learning disability that warrants them lacking the mental capacity to consent.

A forced marriage is not the same as an arranged marriage, where both parties are willing participants.

Honour based abuse and forced marriage are both recognised in law as types of domestic abuse. As such, they should be reported in the same way as other types of domestic abuse if the safeguarding duty applies. This is explained in Section 6, Domestic abuse above.

The affected person can also access help and advice from Karma Nirvana UK. They operate a free and confidential helpline and have a range of other information on their website:

Helpline: 0800 5999 247

Developed with the Forced Marriage Unit, the Virtual College offers a free online awareness course.

Last Updated: August 13, 2025

v75